,Although practical photography dates back almost 2 centuries for much of its early days it was in the hand of the inventors, scientists and entrepreneurs. Then as now, we loved having our photo taken. But in the 19th century that meant a trip to a expensive professional photographer.

But that was radically to change at the start of the 20th Century which would move the camera rapidly from the hands of the “professional” into ours.

Process & Change

There has been much debate about the orgins of the chemical processes behind photography. Some of the first deliberate photographic images were capture abet briefly back well into the 18th century (wikipedia’s article is very helpful if you want to know more). And although there is much debate about whose later techniques should hog the lime light folk like Daguerre and Talbot had given us a B&W chemical process that is still recognisable today.

The problem was that this wasn’t so accessible. You either needed to mix your own chemicals or rely on cumbersome pre-prepared glass plates.

It was George Eastman who changed all of that and led not just to photography for the masses but the movie industry too. In 1884 rather than put a gel of light-sensitive material on glass or soak chemicals into paper, he produced a dry gel on a carrier material. This reduce the weight and hassle of preparing plates and obviously allows for the creation of a roll of film.

Weirdly a Scot Born Farmer living in North Dakota called David Henderson saw this all coming and in 1881 obtained a patent for roll film. He did pretty well out of an idea he never put in to practice and Eastman’s company paid him over $5000USD. (There may also be a link to the to the Kodak name)

Easy Shooting if you can afford it

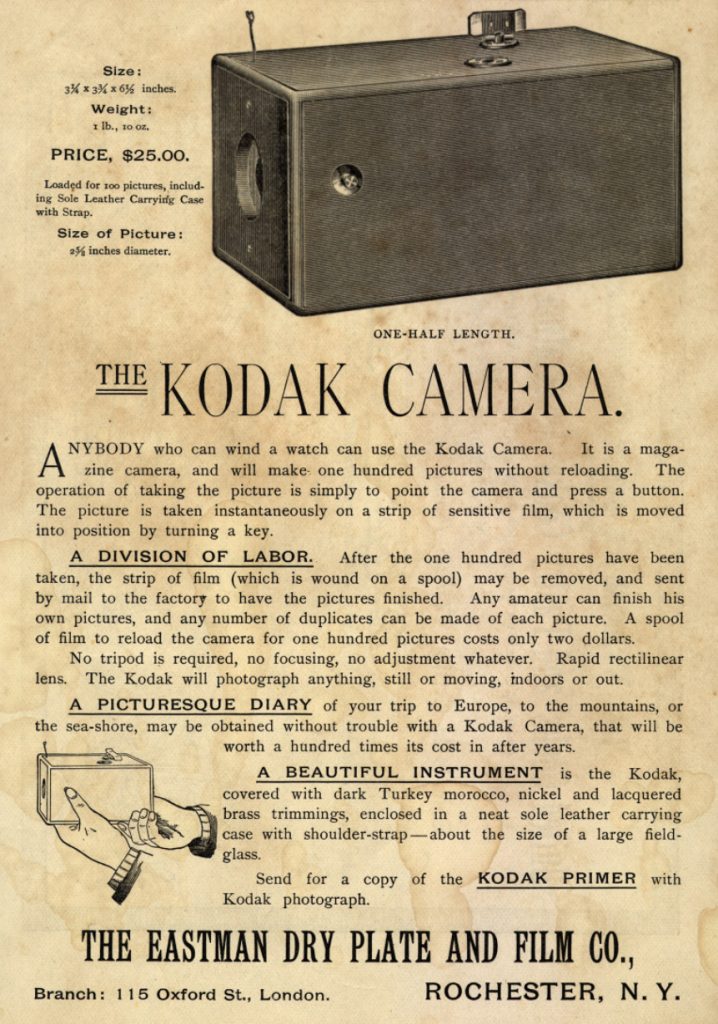

In 1888 Eastman gave us arguably the first camera targeting the public not the professional or wealth enthusiast. The Kodak Camera was a simple fixed focus camera with no viewfinder. Loaded with a a roll allowing for a whooping 100x 2 5/8″ of circular images. Eastman made it easy for you to send the camera back for processing, prints and reloading (although you did have DIY options). There is some speculation that this is the “kodak” that Jonathan Harker uses in Bram Stoker’s 1897 classic Dracula.

But I’ve not started with this. Retailed at $25USD (that’s more than $600 in today’s money), it would be beyond the means of most folk. But George Eastman would soon bring us our starting point

(1) 1900 – Camera for the Masses

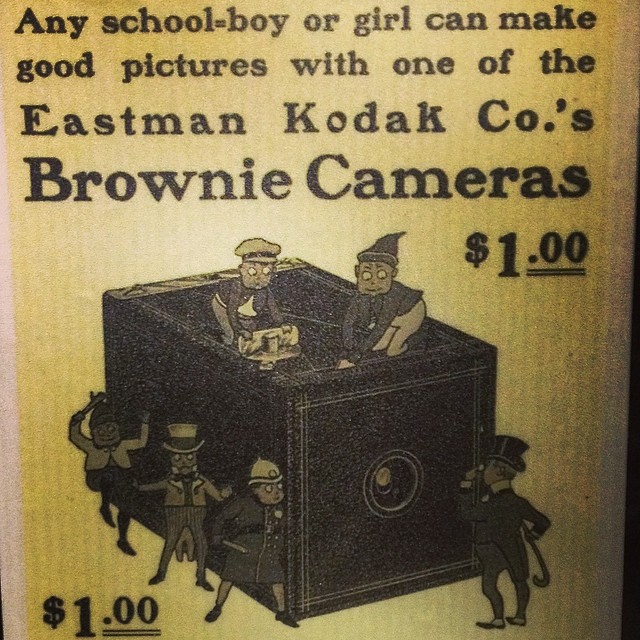

The Kodak Brownie

Arguable the most influential cameras ever made arrived in February 1900 with the original Kodak Brownie. Targeted squarely at the masses this $1 USD camera sold on the razor and blades principle (make the camera cheap and make your money on the film and processing). A very simple box camera made of cardboard with a simple fixed focus meniscus lens.

It sold just shy of a quarter of a million then briefly updated as the Brownie No 1 in 1901. The enduring Brownie No. 2 was launched that year and also gave us medium format 120 film. This camera had one of the longest production runs in history into the mid 30’s and the later metal bodied ones still shoot fine today.

(2) 1912 – The Soldier’s Camera

The Vest Pocket Kodak

From National Library of Scotland’s collection of Earl Haig’s Papers.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Camera unknown

Although Brownie Cameras took many an iconic image of the horrors of WWI, it would be another Kodak sibling that became the camera of the trenches. Kodak had realised by the 1890 that using a collapsible set of bellows allowed them to make more compact cameras.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

The VPK was a big step forward from those first folders. It used a metal not wooden body and the smaller 127 roll film. This made for a camera that you could slip into your uniform pocket.

(3) 1925 – Movie meets Still

The Leica I(A)

The film 135 cassette system was still 9 years away (Kodak get the credit) but the camera whilst clunky also has the features of a typical 35mm viewfinder camera in layout. It is a rare camera and very collectible. It has fixed rather than the interchangeable lens mount later Leicas and is a viewfinder. The camera would not only lead to the fantastic Leica rangefinders of the 30’s and 40’s but also set the standard for 35mm compacts.

(4) 1939 – Another Brick in the wall

Argus C3

With Two million+ bricks sold in a 27 year production run that only paused after Pearl Harbour until the end of WWII was a huge success. The Brick is responsible for many an iconic Americana image and also documented the US at war again.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic License.

Surprisingly durable and still relatively easily sourced. The cameras although can be fiddily are still capable of stunning images.

(5) 1948 – Instant Gratification

Polaroid Land Model 95

Dr Edwin Land and the Polaroid Corp would probably be best remembered for their sunglasses. That is until his daughter Jennifer asked why they had to wait to see their Santa Fe Holiday Photos. This spurned Land into action. In 1947 he demonstrated 1-step (aka instant) photography.

The Model 95 arrived the next year. This used roll film rather than the later square self-contained Polaroids from the 70’s. Selling well over a million Model 95 series cameras, the idea clearly caught the public mood. That was despite the price, you got just 25 cents back from $90USD (about $1000USD today).

(6) 1958 Auto-exposure magic

Fujica 35 Automagic

Kodak had actually given us a working autoexposure camera with the 1938 Kodak Super Six-20. However that camera was too expensive and was a marketing failure. By the end of the 50’s metering electronics had started to become cheaper and built-in light meters were common.

But auto exposure was coming back and this 1958 offering was amongst the first. It looks and feels like a clunky prototype for 1960’s compacts. The auto exposure system is very simple with a single shutter speed, the selenium metering system controls the swinging aperture blades. An interesting abet bulky effort with a not bad Fujinar-K 38mm lens

Just 3 years later Olympus brought out the First PEN EE half frame compact. This was a true point & shoot with a brilliant fix focus lens and a simple but killer auto exposure system. Tiny in comparison to the Automagic but owing it and its rivals a huge debt. The PEN in turn would lead to the 60’s camera icon the Trip 35.

(7) 1963 – Instamatic Plastic

Kodak Hawkeye Instamatic/ Instamatic 50

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

If the Automagic gave us a glimpse of the future, the birth of the instamatic camera in 1963 might have seen somewhat backward. Kodak dreamed up the 126 format which were easy to load cartridges that allowed for cheap but effective cameras. The choice of a frame size of 28x28mm was no coincidence. 126 Cartridges were made from roll film from the ailing 828 roll film line.

Instamatic cameras are now seen as rubbish, cheap, plastic numbers with their inevitable lo-fi images. But they were very popular in the day (Kodak alone sold over 50 million 126 cameras). The frame size is close to that of 35mm leading to some tasty high end 126 cameras including the Rollei SL26 SLR.

The first camera released in the UK was the Instamatic 50 (the Hawkeye version is near identical). Both have a simple fixed focus plastic 43mm 1:11 lens with fixed aperture. A slide adjust the shutter speeds for sunny and cloudy/AG-1 flash bulbs.

Kodak created 2 further easy to load formats – 110 cartridge aka pocket Instamatic in 1972 and the later 1996 collaboration APS. Only 110 of all 3 formats survives having been resurrected by Lomography.

(8) 1977 – Focus Pokus Autofocus

Konica C35AF

The last step to full automation arrived in 1997. Konica’s groundbreaking auto-focus C35AF pipped its closest rival Canon by 18 months to market.

It sensibly used the established C35EF platform for the non AF side of things (the C35EF was the first 35mm camera with an inbuilt electronic flash unit).

The C35AF looks a bit like that C35EF but on steroids. Its passive AF system was a novel Honeywell Visitronic. Most compacts would use an active (often IR based) AF system. Passive AF is more common on more high-end cameras like SLRs. Passive AF works a bit like a rangefinder looking automatically for edge differences via a rangefinder system. However the Honeywell system feels like clockwork. Unlike later passive systems, there is no feedback nor any opportunity to stop taking the photo once triggered.

Meanwhile in 1975 Kodak employees were sticking together a toaster sized camera with a digital sensor rather than film. Although they didn’t realise it, it would spell the doom of their own company and dozens of others……

(9) 1986 P&S completeness

Pentax IQZoom

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic License.

By the time the IQZoom arrived, AF cameras were pretty much becoming the norm for the high and middle consumer markets despite valiant rearguard actions of the likes of the Olympus XA series. But despite the advances you had the choice of a single (or rarely twin) focal length compact camera or splashing out on some not so compact SLR lenses and bodies.

Pentax got in sharp and created the AF compact with a zoom. I use the word compact lightly – compared to later cameras, it is pretty bulky.

The importance of this camera cannot be under estimated. The only other real development that would occur would be replacing film with a digital sensor. Although a modern digital compact is more compact, has dozens of pre programmed shooting modes and improved optics that really is the only major change.

(10) 1995 The ‘New Era’

Casio QV10

That 1970’s Kodak toaster digicam didn’t send rockwaves around the world but its little ripples led to the rise of the digital camera. The QV10 cannot claim to be the first – by the end of the 1970’s we were already using digital sensors on satellites.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Nor can claim in any way to be the first consumer digital. But it was the first to offer a LCD viewing screen. The camera in someways is a backward step. A fixed focus camera with basic optics married to a tichy 0.25MP sensor. The on-board memory is notoriously volatile and hooking it up to your computer is complicated even by 1995 standards. It did at least have auto exposure (abet with only 2 user set apertures). There is no flash and video recording isn’t even an option. However it is a digital camera as we’d all recognise.

It didn’t panic the film world but the ripple were growing larger. It’s also worth noting the names are changing from the well-known camera companies to makers of consumer electronic

……and the bit ?

By the end of 20th Century analogue film was still the master but whilst that slumber Giant continued to blissfully dream the ripples started in 1975 with Kodak’s Heath Robinson Toaster Digicam continue to grow.

By 1998 digital cameras were starting to become more serious. That year Olympus launched the Camedia D-500L & D-600L. These were based on Olympus’s excellent film bridge cameras. These shared the same high quality optics but replaced film with a senor and a removable smart media card. By the end of the decade truly portable dSLR like the Nikon D1 and Fujifilm Finepix S1 Pro arrived. Costs were still high but Digital was now lapping at the ankles and knees of film and would start to overwhelm it by the middle of the next decade.

However just as the 20th Century came to the close – a child of the digital revolution came along that caused another small ripple. Just like the Kodak 1975 digital camera, this would eventually bite the hand that begat it contributing to the partial collapse of the conventional digital camera market.

Oddly not a camera as such….

(the bit or is that bite)

1999 Half phone Half Cam

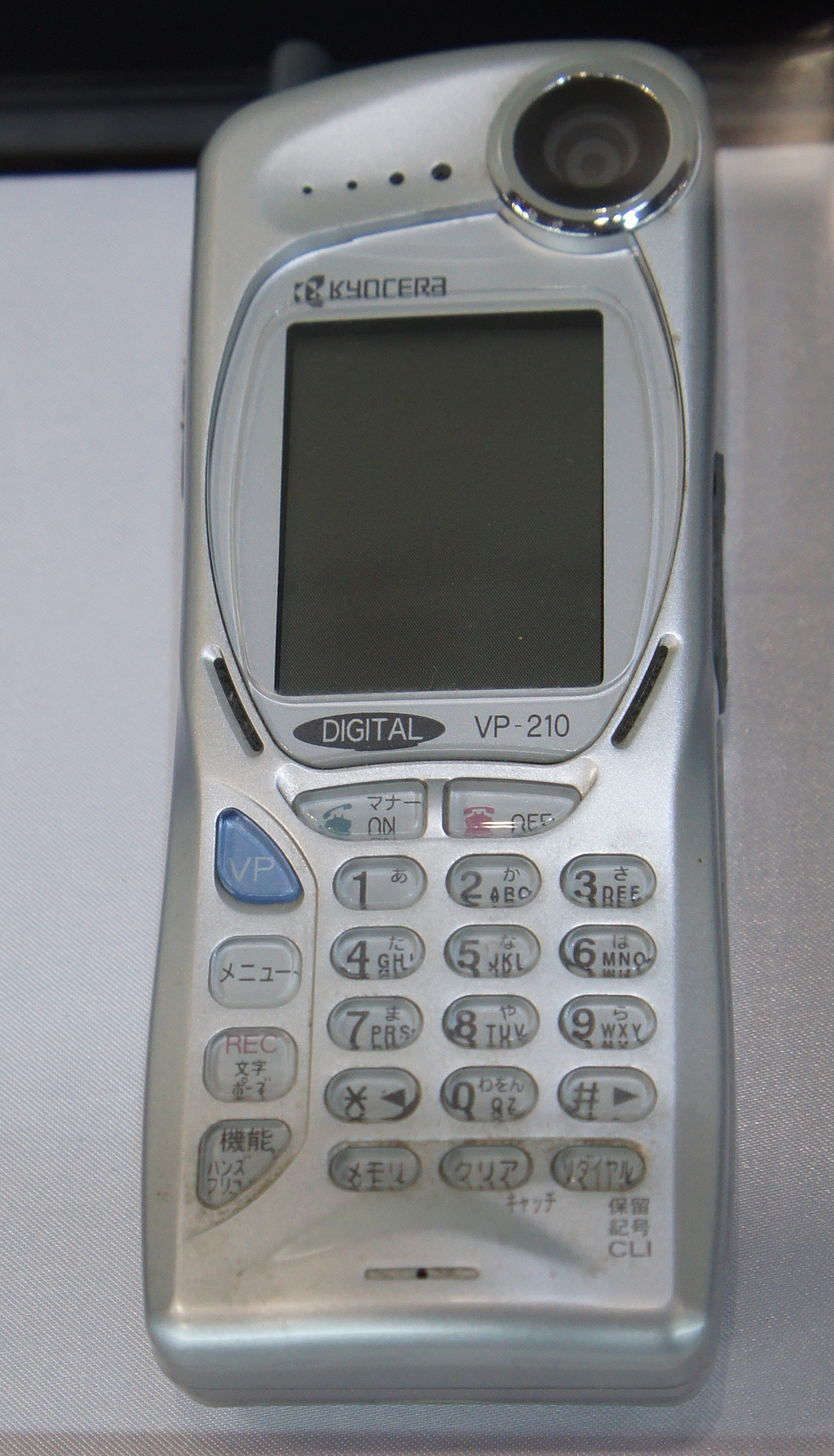

Kyocera VP-210

By the time I type this one person in 3 owns a smartphone. The rise of social media and how news and information is shared has been interlinked with this. No longer are events first caught by professional news crews. It is often the images captured on smartphones by the public that grace our nightly news program headlines.

In 1999 all that was still someway off – this is no modern smartphone. The 0.11MP front facing camera primary use was as a 2fps video phone on Japan’s PHS telephony system. Video conferencing required both users to have a VP-210. The camera also stored up to 20 stills but MMS was not yet a go-er even in Japan so you couldn’t send them

For many of us all this was still the stuff of the science pages of magazines and newspapers. I remember owning the cutting edge technology of a Motorola one touch pager in 1999 !! However within a decade MMS services became standard. We all started taking photos and videos (mainly of our cats and dogs !).

And the rise of the camera phone would also match the rise of social media which arguably began in 1997 with six degrees. Facebook would arrive in 2004 & Instagram by the end of the decade. The arrival of the modern smart phone in 2007 with the iPhone and LG Prada helped drive things further.

And the future ?

The death of film never actually came.

You can still walk onto most British High Streets and buy film. Companies like Lomography are still developing and releasing new cameras and film. A renaissance of Instant film driven by Fujifilm’s instax has led to the re-birth of Polaroid as a viable instant film company. Kodak have just relaunched T-Max P3200.

Dedicated digital camera sales on the other hand have fallen. Just look next time you’re at a gig or event – it’s phones not cameras/ camcorders that people hold up. Why carry a camera when current mobile phone cameras can do the job ? Technological gains have also got more marginal. A dSLR from 10 years ago maybe has a lower MP count and less AF sensor points but is still quite capable of taking quality images. Why upgrade ?